The Earth : Geographical Characteristics [04]

1. Shape and Size

iEduSpace

Earth has a rounded shape, through hydrostatic equilibrium, with an average diameter of 12,742 kilometers (7,918 mi), making it the fifth largest planetary sized and largest terrestrial object of the Solar System.

Due to Earth's rotation it has the shape of an ellipsoid, bulging at its Equator, reaching 43 kilometers (27 mi) further out from its center of mass than at its poles. Earth's shape furthermore has local topographic variations. Though the largest local variations, like the Mariana Trench (10,925 meters or 35,843 feet below local sea level), only shortens Earth's average radius by 0.17% and Mount Everest (8,848 meters or 29,029 feet above local sea level) lengthens it by only 0.14%. Since Earth's surface is farthest out from Earth's center of mass at its equatorial bulge, the summit of the volcano Chimborazo in Ecuador (6,384.4 km or 3,967.1 mi) is its farthest point out. Parallel to the rigid land topography the Ocean exhibits a more dynamic topography.

To measure the local variation of Earth's topography, geodesy employs an idealized Earth producing a shape called a geoid. Such a geoid shape is gained if the ocean is idealized, covering Earth completely and without any perturbations such as tides and winds. The result is a smooth but gravitational irregular geoid surface, providing a mean sea level (MSL) as a reference level for topographic measurements.

2. Surface

the topography of the ocean surface and to a lesser extend of the terrain of Earth's crust above sea level. The larger part of Earth's crust that lies below the ocean hosts the ocean floor at an average bathymetric depth of 4 km and has a terrain as varied as the terrain above sea level. Earth's terrain and landscape is being shaped by internal seismic and volcanic processes, asteroid impacts, wind and temperature weathering, tidal forces, life and the large presence of water and the processes that place and move Earth's water as surface water and ocean water.

Erosion and tectonics, volcanic eruptions, flooding, weathering, glaciation, the growth and decomposition of biomass into soil or other remains such as coral reefs, and meteorite impacts are among the processes that constantly reshape Earth's crust over geological time.

Sedimentary rock is formed from the accumulation of sediment that becomes buried and compacted together. Nearly 75% of the continental surfaces are covered by sedimentary rocks, although they form about 5% of the crust. The third form of rock material found on Earth is metamorphic rock, which is created from the transformation of pre-existing rock types through high pressures, high temperatures, or both. The most abundant silicate minerals on Earth's surface include quartz, feldspars, amphibole, mica, pyroxene and olivine. Common carbonate minerals include calcite (found in limestone) and dolomite.

4. Tectonic Plates

Earth's mechanically rigid outer layer of Earth's crust and upper mantle, the lithosphere, is divided into tectonic plates. These plates are rigid segments that move relative to each other at one of three boundaries types: at convergent boundaries, two plates come together; at divergent boundaries, two plates are pulled apart; and at transform boundaries, two plates slide past one another laterally. Along these plate boundaries, earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation can occur. The tectonic plates ride on top of the asthenosphere, the solid but less-viscous part of the upper mantle that can flow and move along with the plates.

As the tectonic plates migrate, oceanic crust is subducted under the leading edges of the plates at convergent boundaries. At the same time, the upwelling of mantle material at divergent boundaries creates mid-ocean ridges. The combination of these processes recycles the oceanic crust back into the mantle. Due to this recycling, most of the ocean floor is less than 100 Ma old. The oldest oceanic crust is located in the Western Pacific and is estimated to be 200 Ma old. By comparison, the oldest dated continental crust is 4,030 Ma, although zircons have been found preserved as clasts within Eoarchean sedimentary rocks that give ages up to 4,400 Ma, indicating that at least some continental crust existed at that time.

The seven major plates are the Pacific, North American, Eurasian, African, Antarctic, Indo-Australian, and South American. Other notable plates include the Arabian Plate, the Caribbean Plate, the Nazca Plate off the west coast of South America and the Scotia Plate in the southern Atlantic Ocean. The Australian Plate fused with the Indian Plate between 50 and 55 Ma. The fastest-moving plates are the oceanic plates, with the Cocos Plate advancing at a rate of 75 mm/a (3.0 in/year) and the Pacific Plate moving 52–69 mm/a (2.0–2.7 in/year). At the other extreme, the slowest-moving plate is the South American Plate, progressing at a typical rate of 10.6 mm/a (0.42 in/year).

4. Internal Structure

Earth's interior, like that of the other terrestrial planets, is divided into layers by their chemical or physical (rheological) properties. The outer layer is a chemically distinct silicate solid crust, which is underlain by a highly viscous solid mantle. The crust is separated from the mantle by the Mohorovičić discontinuity. The thickness of the crust varies from about 6 kilometers (3.7 mi) under the oceans to 30–50 km (19–31 mi) for the continents. The crust and the cold, rigid, top of the upper mantle are collectively known as the lithosphere, which is divided into independently moving tectonic plates.

Beneath the lithosphere is the asthenosphere, a relatively low-viscosity layer on which the lithosphere rides. Important changes in crystal structure within the mantle occur at 410 and 660 km (250 and 410 mi) below the surface, spanning a transition zone that separates the upper and lower mantle. Beneath the mantle, an extremely low viscosity liquid outer core lies above a solid inner core. Earth's inner core may be rotating at a slightly higher angular velocity than the remainder of the planet, advancing by 0.1–0.5° per year, although both somewhat higher and much lower rates have also been proposed. The radius of the inner core is about one-fifth of that of Earth. Density increases with depth, as described in the table on the right.

Among the Solar System's planetary-sized objects Earth is the object with the highest density.

5. Chemical Composition

Earth's mass is approximately 5.97×1024 kg (5,970 Yg). It is composed mostly of iron (32.1% by mass), oxygen (30.1%), silicon (15.1%), magnesium (13.9%), sulfur (2.9%), nickel (1.8%), calcium (1.5%), and aluminum (1.4%), with the remaining 1.2% consisting of trace amounts of other elements. Due to gravitational separation, the core is primarily composed of the denser elements: iron (88.8%), with smaller amounts of nickel (5.8%), sulfur (4.5%), and less than 1% trace elements. The most common rock constituents of the crust are oxides. Over 99% of the crust is composed of various oxides of eleven elements, principally oxides containing silicon (the silicate minerals), aluminum, iron, calcium, magnesium, potassium, or sodium.

6. Internal Heat

The major heat-producing isotopes within Earth are potassium-40, uranium-238, and thorium-232. At the center, the temperature may be up to 6,000 °C (10,830 °F), and the pressure could reach 360 GPa (52 million psi). Because much of the heat is provided by radioactive decay, scientists postulate that early in Earth's history, before isotopes with short half-lives were depleted, Earth's heat production was much higher. At approximately 3 Gyr, twice the present-day heat would have been produced, increasing the rates of mantle convection and plate tectonics, and allowing the production of uncommon igneous rocks such as komatiites that are rarely formed today.

The mean heat loss from Earth is 87 mW m−2, for a global heat loss of 4.42×1013 W. A portion of the core's thermal energy is transported toward the crust by mantle plumes, a form of convection consisting of upwellings of higher-temperature rock. These plumes can produce hotspots and flood basalts. More of the heat in Earth is lost through plate tectonics, by mantle upwelling associated with mid-ocean ridges. The final major mode of heat loss is through conduction through the lithosphere, the majority of which occurs under the oceans because the crust there is much thinner than that of the continents.

7. Gravitational Field

The gravity of Earth is the acceleration that is imparted to objects due to the distribution of mass within Earth. Near Earth's surface, gravitational acceleration is approximately 9.8 m/s2 (32 ft/s2). Local differences in topography, geology, and deeper tectonic structure cause local and broad regional differences in Earth's gravitational field, known as gravity anomalies.

8. Magnetic Field

The main part of Earth's magnetic field is generated in the core, the site of a dynamo process that converts the kinetic energy of thermally and compositionally driven convection into electrical and magnetic field energy. The field extends outwards from the core, through the mantle, and up to Earth's surface, where it is, approximately, a dipole. The poles of the dipole are located close to Earth's geographic poles. At the equator of the magnetic field, the magnetic-field strength at the surface is 3.05×10−5 T, with a magnetic dipole moment of 7.79×1022 Am2 at epoch 2000, decreasing nearly 6% per century (although it still remains stronger than its long time average). The convection movements in the core are chaotic; the magnetic poles drift and periodically change alignment. This causes secular variation of the main field and field reversals at irregular intervals averaging a few times every million years. The most recent reversal occurred approximately 700,000 years ago.

The extent of Earth's magnetic field in space defines the magnetosphere. Ions and electrons of the solar wind are deflected by the magnetosphere; solar wind pressure compresses the dayside of the magnetosphere, to about 10 Earth radii, and extends the nightside magnetosphere into a long tail. Because the velocity of the solar wind is greater than the speed at which waves propagate through the solar wind, a supersonic bow shock precedes the dayside magnetosphere within the solar wind. Charged particles are contained within the magnetosphere; the plasmasphere is defined by low-energy particles that essentially follow magnetic field lines as Earth rotates. The ring current is defined by medium-energy particles that drift relative to the geomagnetic field, but with paths that are still dominated by the magnetic field, and the Van Allen radiation belts are formed by high-energy particles whose motion is essentially random, but contained in the magnetosphere.

During magnetic storms and substorms, charged particles can be deflected from the outer magnetosphere and especially the magnetotail, directed along field lines into Earth's ionosphere, where atmospheric atoms can be excited and ionized, causing the aurora.

9. Hydrosphere

Earth's hydrosphere is the sum of Earth's water and its distribution. Most of Earth's hydrosphere consists of Earth's global ocean. Nevertheless, Earth's hydrosphere also consists of water in the atmopshere and on land, including clouds, inland seas, lakes, rivers, and underground waters down to a depth of 2,000 m (6,600 ft). The mass of the oceans is approximately 1.35×1018 metric tons or about 1/4400 of Earth's total mass. The oceans cover an area of 361.8 million km2 (139.7 million sq mi) with a mean depth of 3,682 m (12,080 ft), resulting in an estimated volume of 1.332 billion km3 (320 million cu mi). If all of Earth's crustal surface were at the same elevation as a smooth sphere, the depth of the resulting world ocean would be 2.7 to 2.8 km (1.68 to 1.74 mi). About 97.5% of the water is saline; the remaining 2.5% is fresh water. Most fresh water, about 68.7%, is present as ice in ice caps and glaciers. The remaining 30% is ground water, 1% surface water (covering only 2.8% of Earth's land) and other small forms of fresh water deposits such as permafrost, water vapor in the atmosphere, biological binding, etc.

In Earth's coldest regions, snow survives over the summer and changes into ice. This accumulated snow and ice eventually forms into glaciers, bodies of ice that flow under the influence of their own gravity. Alpine glaciers form in mountainous areas, whereas vast ice sheets form over land in polar regions. The flow of glaciers erodes the surface changing it dramatically, with the formation of U-shaped valleys and other landforms. Sea ice in the Arctic covers an area about as big as the United States, although it is quickly retreating as a consequence of climate change.

The average salinity of Earth's oceans is about 35 grams of salt per kilogram of seawater (3.5% salt). Most of this salt was released from volcanic activity or extracted from cool igneous rocks. The oceans are also a reservoir of dissolved atmospheric gases, which are essential for the survival of many aquatic life forms. Sea water has an important influence on the world's climate, with the oceans acting as a large heat reservoir. Shifts in the oceanic temperature distribution can cause significant weather shifts, such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation.

The abundance of water, particularly liquid water, on Earth's surface is a unique feature that distinguishes it from other planets in the Solar System. Solar System planets with considerable atmospheres do partly host atmospheric water vapor, but they lack surface conditions for stable surface water. Despite some moons showing signs of large reservoirs of extraterrestrial liquid water, with possibly even more volume than Earth's ocean, all of them are large bodies of water under a kilometers thick frozen surface layer.

10. Atmosphere

The atmospheric pressure at Earth's sea level averages 101.325 kPa (14.696 psi), with a scale height of about 8.5 km (5.3 mi). A dry atmosphere is composed of 78.084% nitrogen, 20.946% oxygen, 0.934% argon, and trace amounts of carbon dioxide and other gaseous molecules. Water vapor content varies between 0.01% and 4% but averages about 1%. Clouds cover around two thirds of Earth's surface, more so over oceans than land. The height of the troposphere varies with latitude, ranging between 8 km (5 mi) at the poles to 17 km (11 mi) at the equator, with some variation resulting from weather and seasonal factors.

Earth's biosphere has significantly altered its atmosphere. Oxygenic photosynthesis evolved 2.7 Gya, forming the primarily nitrogen–oxygen atmosphere of today. This change enabled the proliferation of aerobic organisms and, indirectly, the formation of the ozone layer due to the subsequent conversion of atmospheric O2 into O3. The ozone layer blocks ultraviolet solar radiation, permitting life on land. Other atmospheric functions important to life include transporting water vapor, providing useful gases, causing small meteors to burn up before they strike the surface, and moderating temperature. This last phenomenon is the greenhouse effect: trace molecules within the atmosphere serve to capture thermal energy emitted from the surface, thereby raising the average temperature. Water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone are the primary greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Without this heat-retention effect, the average surface temperature would be −18 °C (0 °F), in contrast to the current +15 °C (59 °F), and life on Earth probably would not exist in its current form.

11. Weather and Climate

Earth's atmosphere has no definite boundary, gradually becoming thinner and fading into outer space. Three-quarters of the atmosphere's mass is contained within the first 11 km (6.8 mi) of the surface; this lowest layer is called the troposphere. Energy from the Sun heats this layer, and the surface below, causing expansion of the air. This lower-density air then rises and is replaced by cooler, higher-density air. The result is atmospheric circulation that drives the weather and climate through redistribution of thermal energy.

The primary atmospheric circulation bands consist of the trade winds in the equatorial region below 30° latitude and the westerlies in the mid-latitudes between 30° and 60°. Ocean heat content and currents are also important factors in determining climate, particularly the thermohaline circulation that distributes thermal energy from the equatorial oceans to the polar regions.

Earth receives 1361 W/m2 of solar irradiance. The amount of solar energy that reaches the Earth's surface decreases with increasing latitude. At higher latitudes, the sunlight reaches the surface at lower angles, and it must pass through thicker columns of the atmosphere. As a result, the mean annual air temperature at sea level decreases by about 0.4 °C (0.7 °F) per degree of latitude from the equator. Earth's surface can be subdivided into specific latitudinal belts of approximately homogeneous climate. Ranging from the equator to the polar regions, these are the tropical (or equatorial), subtropical, temperate and polar climates.

Further factors that affect a location's climates are its proximity to oceans, the oceanic and atmospheric circulation, and topology. Places close to oceans typically have colder summers and warmer winters, due to the fact that oceans can store large amounts of heat. The wind transports the cold or the heat of the ocean to the land. Atmospheric circulation also plays an important role: San Francisco and Washington DC are both coastal cities at about the same latitude. San Francisco's climate is significantly more moderate as the prevailing wind direction is from sea to land. Finally, temperatures decrease with height causing mountainous areas to be colder than low-lying areas.

Water vapor generated through surface evaporation is transported by circulatory patterns in the atmosphere. When atmospheric conditions permit an uplift of warm, humid air, this water condenses and falls to the surface as precipitation. Most of the water is then transported to lower elevations by river systems and usually returned to the oceans or deposited into lakes. This water cycle is a vital mechanism for supporting life on land and is a primary factor in the erosion of surface features over geological periods. Precipitation patterns vary widely, ranging from several meters of water per year to less than a millimeter. Atmospheric circulation, topographic features, and temperature differences determine the average precipitation that falls in each region.

The commonly used Köppen climate classification system has five broad groups (humid tropics, arid, humid middle latitudes, continental and cold polar), which are further divided into more specific subtypes. The Köppen system rates regions based on observed temperature and precipitation. Surface air temperature can rise to around 55 °C (131 °F) in hot deserts, such as Death Valley, and can fall as low as −89 °C (−128 °F) in Antarctica.

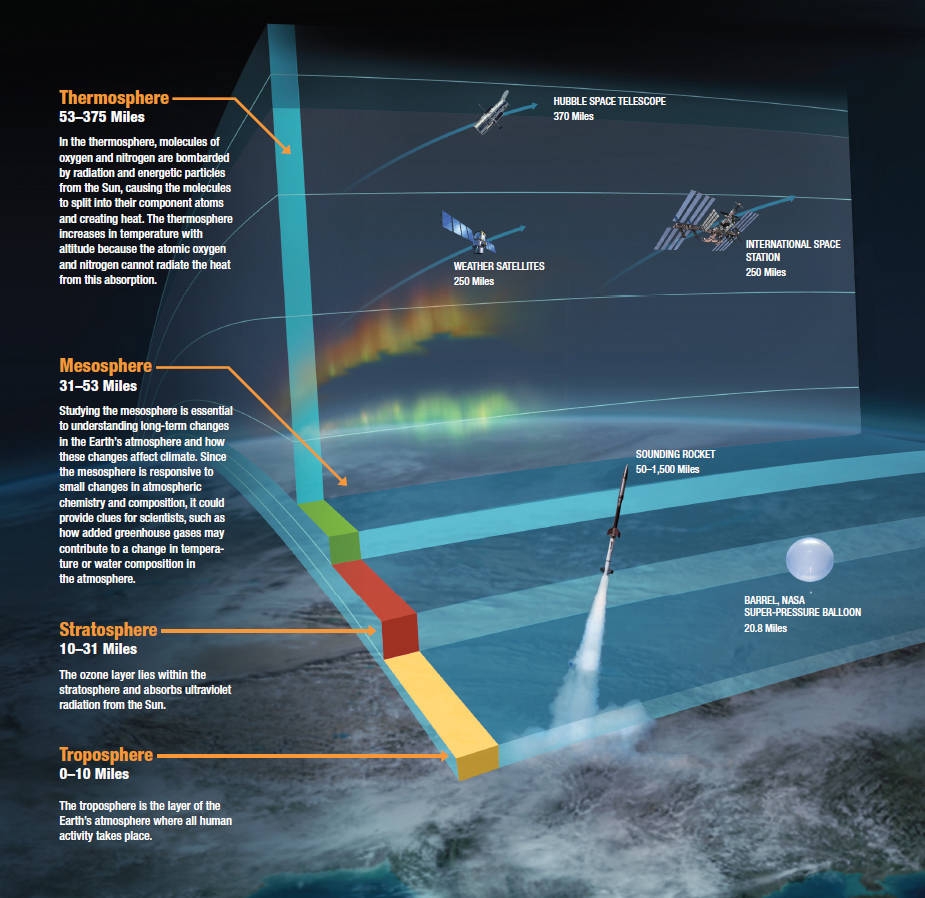

12. Upper Atmosphere

The upper atmosphere, the atmosphere above the troposphere, is usually divided into the stratosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere. Each layer has a different lapse rate, defining the rate of change in temperature with height. Beyond these, the exosphere thins out into the magnetosphere, where the geomagnetic fields interact with the solar wind. Within the stratosphere is the ozone layer, a component that partially shields the surface from ultraviolet light and thus is important for life on Earth. The Kármán line, defined as 100 km (62 mi) above Earth's surface, is a working definition for the boundary between the atmosphere and outer space.

Thermal energy causes some of the molecules at the outer edge of the atmosphere to increase their velocity to the point where they can escape from Earth's gravity. This causes a slow but steady loss of the atmosphere into space. Because unfixed hydrogen has a low molecular mass, it can achieve escape velocity more readily, and it leaks into outer space at a greater rate than other gases. The leakage of hydrogen into space contributes to the shifting of Earth's atmosphere and surface from an initially reducing state to its current oxidizing one. Photosynthesis provided a source of free oxygen, but the loss of reducing agents such as hydrogen is thought to have been a necessary precondition for the widespread accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere. Hence the ability of hydrogen to escape from the atmosphere may have influenced the nature of life that developed on Earth. In the current, oxygen-rich atmosphere most hydrogen is converted into water before it has an opportunity to escape. Instead, most of the hydrogen loss comes from the destruction of methane in the upper atmosphere.

Thanks for Read My Blog.

At is Platform you will get more and more detailed information about Our Solar system, Galaxies, All Planets and Universe. For the interesting informations about our universe. Follow this website i_eduspace

Stay Tuned......

By- Navneet Patidar

Special Thanks:

Images from NASA & ISRO

Content from Wikipedia

iEDUSPACE--Expand Your Cosmic Knowledge with Us

Comments

Post a Comment